Kareem Abdullah : pagina di storia memorabile di grande dolore e di facile immedesimazione per chiunque è mamma e vive nell’ attesa del ritorno del figlio dalla guerra.

È doveroso leggere questi contenuti che appartengono alla società e stimato scrittore per aver condiviso.

Ecco perché i ritorni sono in ritardo… Perché non ritornano più.

Questo è mio figlio, signore— la sua voce all’alba era la prima cosa a svegliare gli uccelli dai loro sogni. Era solito ridere quando cadeva la pioggia, come se ricordasse al cielo il suo desiderio di partorire di nuovo.

Questo è mio figlio, signore— teneva una pagnotta di pane in una mano e l’infanzia nell’altra. Non sapeva nulla della guerra se non quello che vedeva dai notiziari serali e nulla della morte se non quello che veniva detto nei sermoni funebri.

Ma un giorno… se ne andò, partì affinché fosse restituito uomo — e non tornò mai più.

La guerra è finita, o almeno così annuncia la radio, ma mio figlio non è tornato. Come se i proiettili lo avessero inghiottito intero, come se i cannoni lo avessero nascosto nel profondo, come se la terra si fosse affezionata a lui e si fosse rifiutata di lasciarlo andare.

Posso rivelarle un segreto, signore? Le madri non credono agli annunci della vittoria. Poiché la vittoria non si misura dal numero di stendardi issati, ma dal numero di figli che tornano a cena senza che le loro anime vengano conteggiate insieme al bottino!

Questo è mio figlio, signore— Chiedo solo che mi venga restituito così com’era : con mezzo livido, o mezzo braccio, o anche solo la sua voce gracchiante attraverso un telefono rotto, con la sua ombra proiettata sopra un muro, o con la sua foto bruciata nella tasca di qualche soldato sopravvissuto— Ma non è mai tornato!

Sapete chi torna dalle guerre? Solo i leader! Solo i leader, signore, ritornano— con le loro cravatte dritte, i loro abiti stirati e i loro sorrisi falsi alle conferenze di pace. Tornano per scrivere lettere di perdono e per consegnarci medaglie sulle tombe di coloro che amiamo.

Quanto ai miei figli… non sanno come tornare, Perché la Patria ha dimenticato come riportare indietro i suoi figli senza prima seppellirli.

E io— porto la sua foto come una madre porta la bara del mondo. Leggo i volti dei bambini per strada, cerco i suoi occhi negli sconosciuti di passaggio e ascolto la sua voce sul mio respiro—

nella speranza che la vita, per vergogna, possa confessare di averlo rubato.

Signore, questo è mio figlio, che se n’è

andato in una mattina tranquilla

e non tornò mai più quella sera. Forse inciampò nella luce di una granata, o si allontanò dal sentiero di casa, o si perse nell’inno nazionale… Ma non tornò.

E ancora, lei dice: La guerra è finita.

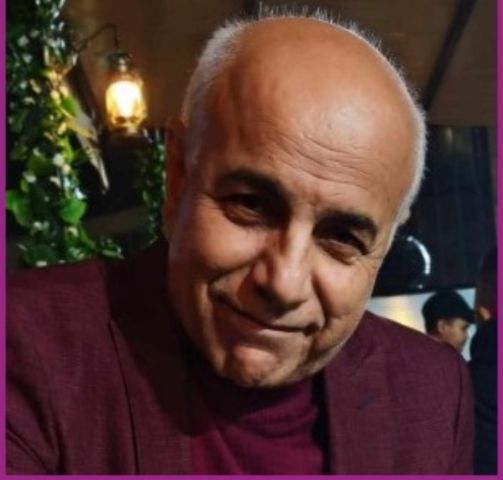

Karim Abdullah – Iraq

Lettura poetica in italiano a cura di Elisa Mascia -Italia

This Is Why the Returning Are Late… Because They Do Not Return

This is my son, sir— his voice at dawn was the first thing to wake the birds from their dreams. He used to laugh when the rain would fall, as if reminding the sky of its desire to give birth again.

This is my son, sir— he held bread in one hand, and childhood in the other. He knew war only from the evening news, and death only from funeral speeches.

But one day… he left, left to return a man — and never came back.

The war is over, or so the radio says, but my son did not return. As if the bullets had swallowed him whole, as if the cannons had hidden him deep within, as if the earth took a liking to him and refused to let him go.

Shall I tell you a secret, sir? Mothers don’t believe the news of victory. For victory is not counted in flags raised, but in sons returning to dinner without their souls tallied among the spoils.

This is my son, sir— I ask for nothing but his return, as he was: with half a bruise, or half an arm, or even just his voice crackling through a broken phone, his shadow cast on a wall, or a burned photo tucked in the pocket of some surviving soldier— but he did not return.

Do you know what comes back from war? Only the leaders, sir. Only the leaders return— with their neckties straight, their suits pressed, and their borrowed smiles in peace summits. They return to write speeches of forgiveness, and pin medals on the graves of those we love.

But my sons… they do not know how to return. For the homeland has forgotten how to bring its sons back without first burying them.

And I— I carry his picture like a mother carries the coffin of the world. I read the faces of children in the streets, search for his eyes in passing strangers, and draw his voice over my breath—

in hopes that life, out of shame, might confess it had stolen him.

Sir, this is my son, who left on a quiet morning

and never returned that evening. Perhaps he stumbled into the light of a shell, or strayed from the path home, or lost himself in the anthem of the nation— But he did not return.

And still, you say: The war is over.

Karim Abdullah -Iraq

هكذا يتأخر العائدون… لأنهم لا يعودون

هذا ابني يا سيدي، كان صوته في الفجر أوّل ما يُوقظ العصافير من حلمها، وكان يضحكُ حين يسقط المطر، كأنه يُعيد للسماء رغبتها في الولادة.

هذا ابني يا سيدي، كان يحملُ رغيفًا في يده، وطفولةً في الأخرى، لا يعرف من الحرب إلا ما يشاهده في نشرة الأخبار ولا من الموت إلا ما يُقال في خطب الجنازات.

لكنه خرج… خرج ذات يومٍ ليعود رجلاً — وما عاد!

الحرب انتهت، أو هكذا قال المذياع، لكن ابني لم يعد! كأنّ الطلقات ابتلعته، كأنّ المدافع خبّأته في جوفها، كأنّ الأرض استحسنته ولم تُرد أن تُفرّط فيه.

هل أخبركَ بسرّ، يا سيدي؟ الأمهات لا يصدّقن نشرة الانتصار، لأن النصر لا يُقاس بعدد الرايات، بل بعدد الأبناء العائدين إلى العشاء دون أن تُعدّ أرواحهم مع الغنائم!

هذا ابني يا سيدي، أنا لا أطلب سوى أن يُعاد إليّ كما كان: بنصف كدمة، أو نصف ذراع، أو حتى بصوته في هاتفٍ مقطوع، بظلّه على الجدار، أو بصورته محروقة في جيب مقاتلٍ ناجٍ… لكنّه لم يعد!

أتعرف ما الذي يعود من الحروب؟ لا يعود سوى القادة! القادة فقط، يا سيدي، يعودون بربطات أعناقهم، وملابسهم المكويّة، وابتساماتهم المستعارة في مؤتمرات السلام، يعودون ليكتبوا خطابات الغفران، ويمنحونا أوسمةً على قبور من نحب.

أما أبنائي… فهم لا يُجيدون العودة، لأنّ الوطن نسي كيف يُعيد أبناءه دون أن ينساهم في المقابر. وأنا؟ أحملُ صورتَه كأمٍّ تحمل تابوتَ العالم، أقرأ وجوه الأطفال في الطرقات، أبحث عن عينيه في المارّين، وأرسم صوته فوق لهاثي… لعلّ الحياة تخجل وتعترف أنها سرقته.

يا سيدي، هذا ابني الذي خرج في صباحٍ هادئ ولم يعد في المساء، ربما تعثّر في ضوء القذيفة، أو سها عن درب العودة، أو تاه في نشيد الوطن…

لكنه لم يعد، وأنتم تقولون: الحربُ انتهت.

Kareem Abdullah -Iraq

Recensione della poetessa Salwa Hussein Ali

Il testo utilizza metafore e immagini potenti, creando scene vivide nella mente del lettore, come se catturasse il battito dell’anima di una madre.

Il dolore non è forzato; sembra scaturire dalle profondità di un’anima che ha sofferto e perso la cosa più preziosa che possiede.

La ripetizione della frase “Questo è mio figlio, signore” conferisce al testo un ritmo che ricorda un’elegia o una preghiera, sottolineando l’identità umana della vittima, come se la madre cercasse di ricordare al mondo che suo figlio non era solo un numero.

Questo testo è creativo, potente e doloroso. Riesce a trasmettere pura sofferenza umana, lontano da qualsiasi slogan o ideologia, e a dimostrare che il vero prezzo della guerra non viene pagato da politici o generali, ma da madri, padri e figli in silenzio.

Review by poet Salwa Hussein Ali

The text uses powerful metaphors and imagery, creating vivid scenes in the reader’s mind, as if capturing the pulse of a mother’s soul.

The pain isn’t contrived; it seems to spring from the depths of a soul that has suffered and lost the most precious thing it possesses.

The repetition of the phrase “This is my son, sir” gives the text a rhythm resembling an elegy or a prayer, emphasizing the victim’s human identity, as if the mother is trying to remind the world that her son was not just a number.

This text is creative, powerful, and painful. It succeeds in conveying pure human suffering, far removed from any slogans or ideologies, and in demonstrating that the true price of war is not paid by politicians or generals, but by mothers, fathers, and sons in silence.

مراجعة للشاعرة سلوى حسين علي

النص یستخدم استعارات ومجازات قویة ، تخلق مشاهد حیة في ذهن القارئ كما یستخدم نبض روح ٲم.

الألم ليس مُفتعلاً، بل يبدو نابعاً من أعماق روح عانت وخسرت أغلى ما لديها.

تكرار جملة “هذا ابني يا سيدي” يعطي النص إيقاعاً يشبه المرثية أو الصلاة، ويؤكد على الهوية الإنسانية للضحية، وكأن الأم تحاول تذكير العالم بأن ابنها لم يكن مجرد رقم.

هذا النص مبدع وقوي ومؤلم. نجح في نقل المعاناة الإنسانية الخالصة بعيداً عن أي شعارات أو أيديولوجيات و بأن الثمن الحقيقي للحرب لا يدفعه السياسيون أو الجنرالات، بل يدفعه الأمهات والآباء والأبناء في صمت.